What is Major Depression?

What does it mean to be depressed?

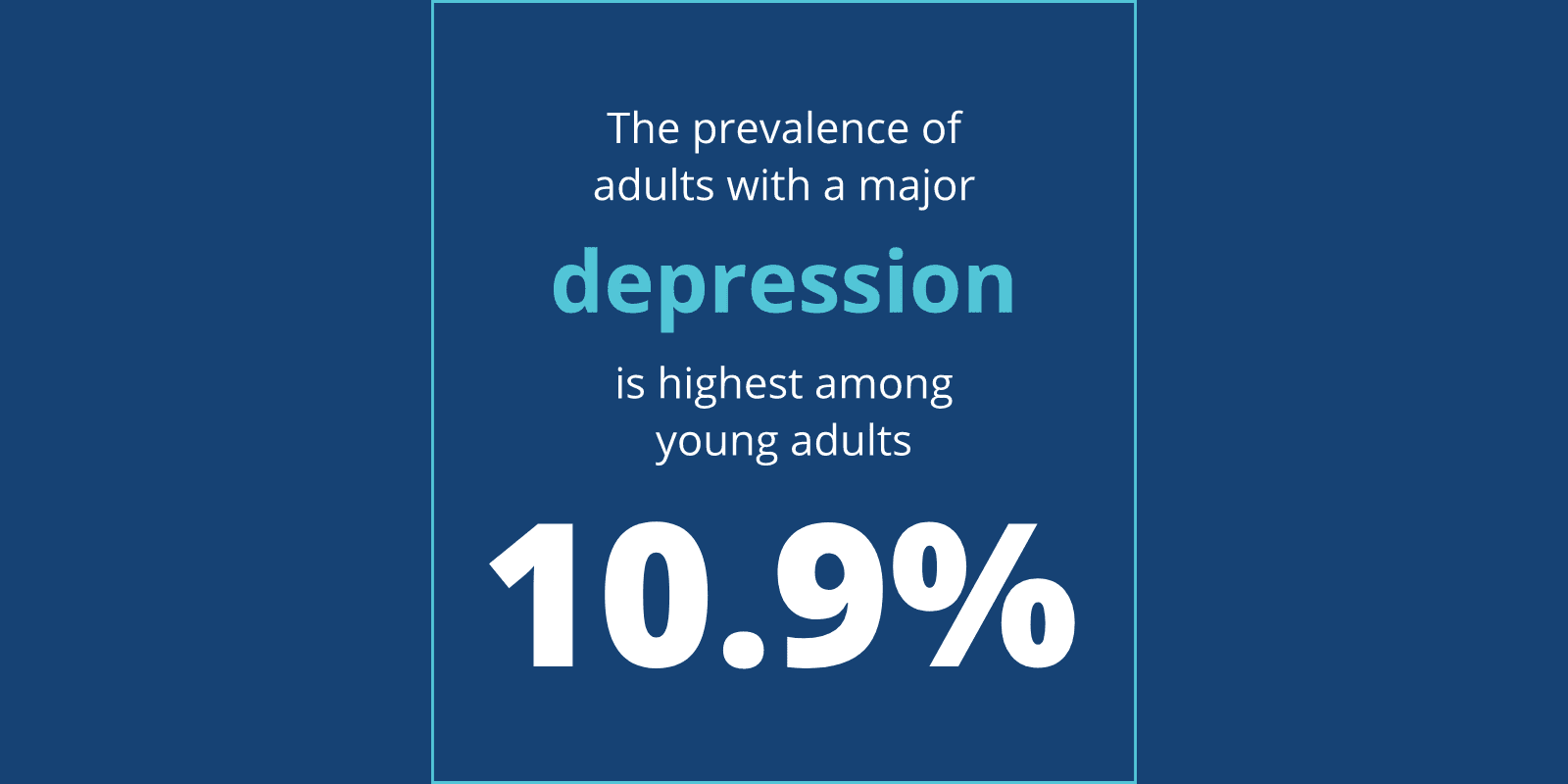

People use this term to describe someone’s mood – maybe your teen or young adult is going through an unusually difficult time in their life, or they’re having a bout of the blues. But if there wasn’t any catalyst for their behavior, or the symptoms are more of the norm than the exception, it’s possible that your child could be battling what’s known as major depressive disorder.

To help with this differentiation, we can look at how the clinical world defines major depression. An important factor to pay attention to is time: situational depression comes and goes, eventually dissipating. But during a major depressive episode, your child would experience some of the symptoms listed below nearly every day for at least two weeks:

- Insomnia (not sleeping enough) or hypersomnia (sleeping to much)

- Change of more than 5 percent of their body weight in less than a month

- Impaired concentration

- Indecisiveness

- Feelings of worthlessness or guilt nearly every day

Your child might be sleeping excessively or not at all, losing a significant amount of weight when not purposefully dieting, fatigued all the time, losing pleasure in activities they used to enjoy or skipping school. Two of the most important depression symptoms to be aware of are hopelessness and recurrent thoughts of death.

How Can I Tell the Difference Between Depression and Sadness?

Everyone feels sad from time to time. It’s normal to feel sad in response to an event that triggers feelings of disappointment, loss, grief, heartache or pain. And after a period of time, when you’ve worked through your feelings and have some distance from the situation, that sadness fades.

Depression, on the other hand, is a state of feeling sad all the time. It’s not necessarily in response to anything; it just is. It permeates everything – the way your child thinks, perceives the people they interact with and the world around them, and the way they act. Rather than feeling sad as a response to something specific, they feel sad in general.

Depression and Suicide in Young People – and When to Say Something

It’s difficult to talk about major depressive disorder without including a discussion about suicide. We see it in the media and in those around us who have been affected by it. We as a society know all too well that no demographic is immune to the impact clinical depression can have.

Loved ones of people struggling with depression are often concerned that if they ask someone if they’re feeling suicidal, they might be planting the idea in their head. This just isn’t the case – in fact, research tells us exactly the opposite.

Talking to your kid about suicide can have a profound effect, and can give them the opportunity to voice some worrying thoughts they’re having. Being direct is important – it might be uncomfortable, but asking a question like, “Have you ever thought of suicide?” can make all the difference.

Risk Factors for Depressive Disorders

Studies have shown that genetic predisposition is a key risk factor for major depressive disorder. If a first-degree relative has major depression, there’s a much higher likelihood that your child could develop it as well.

Mental disorders aren’t easy to diagnose, and major depression is no different – sometimes it occurs due to genetically inherited chemical imbalances; other times it’s a result of your child’s environment or a traumatic experience they’ve had. What’s important is that, regardless of its reasons for occurring, it has real impact.

Depression and Self-Harm

One way depressed people act out is to harm themselves – by cutting, burning, hitting, scratching, puncturing, picking or other methods. Far from the cry for attention it’s often perceived to be, this behavior actually has a few reasons behind it.

Physically, the pain causes an endorphin release, which in turn gives the person doing it a distraction and temporary relief from the emotional pain they’re going through. Symbolically, it’s also a way of expressing the pain they feel, because they can’t do so verbally or in other, healthier ways. Most people who harm themselves do so in order to:

- Distract from their emotional distress

- Jolt themselves out of their apathy

- Regain a small sense of control

- Express their overwhelming emotions

- Self-flagellate out of shame

- Express the pain they can’t otherwise communicate

Self-harm is not suicidal, but it can be dangerous. And it’s more common than you may think – an estimated 4 percent of people in the US self-injure as a result of depression or other emotional distress, though most people go to great lengths to hide it. Most people start self-harming when they are teenagers.

How Depression is Treated

The good news is that depression can be treated very effectively. The National Institute of Mental Health found that with the right combination of antidepressant medication, psychotherapy and support groups, 80 percent of patients improved their depression symptoms within four to six weeks.

However, being that each teen is unique, the same treatment doesn’t work for everyone. If you’ve tried treatment methods in the past and haven’t seen results, don’t get discouraged. Your biggest breakthrough could be just around the corner.

What Can You do to Help Your Depressed Teen or Young Adult?

If you’re struggling to parent a depressed teenager, you’re certainly not alone. Here are some steps you can take to start making your way out of the dark:

- Join parent support groups – Dealing with a depressed or suicidal teen is an isolating experience, and it’s important that you find someone you can relate to about it so you don’t feel like you’re alone. Look into mental health organizations and community centers that host local parent meetings. Sandstone Care offers a free, weekly support group for parents just like you.

- Enroll in therapy – You may feel like you don’t want to burden people in your usual support network with the weight of your problems. Talking to a counselor is a great way to vent, get professional advice and receive extra support.

- Track your teen’s depression – Help your child keep a log that records the timing and duration of their depression. This will help them more accurately convey their experience to their counselor and get the most out of treatment.

Remember, there is light at the end of the tunnel. Many people struggle with depression and find effective ways to overcome it. If you’re unsure of what to do to help your depressed child, Sandstone Care can help.

Our highly trained and experienced team is passionate about promoting mental wellness in youth, and our open, non-judgmental environment lets young people feel like they can truly be themselves. Call us seven days a week at (888) 850-1890 to learn what treatment options are available that could help your family.

Parents’ Corner

It’s impossible to overstate how isolating parenting a severely depressed or suicidal teen can be. It’s crucial to find parents you can relate to about your experience – which means you may need to look outside of your normal support network. Here are some resources that may help:

Your Local YMCA

The YMCA’s Youth and Family Services department offers several programs aimed at strengthening families and improving communication between parents and teens.

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI)

The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) offers support for families of teens with mental illnesses, including local groups and online resources.

The Balanced Mind Parent Network

Created by the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (DBSA), this program provides a host of resources for parents of depressed teens, including online and in-person support groups.

Sandstone Care’s Parent Support Group

We provide a judgment-free space where parents can share their thoughts, feelings and experiences and listen to those of others. Free groups are hosted weekly and facilitated by an experienced Sandstone Care clinician. We’ll discuss topics like challenges, support and self-care. See our parent support group locations and times here.

Family Treatment

To improve the quality of life as a family, it’s essential to involve the entire family in treatment. We have individual family therapy, multi-family groups, and parent support groups. Here, families will find a space where they have permission to be open and honest about the challenges they are facing. They can also find answers about mental health and what treatment looks like at Sandstone Care.

We’re available 7 days a week to help answer any questions you may have.

Our Accreditations