Michael Dinneen, of Shadow Mountain Recovery, has been in the addiction and recovery world for over 25 years, in both a personal and professional capacity.

We sat down for lunch to talk about his own journey, how his understanding of addiction and recovery have evolved, and the nuances of working with young adults and process addictions.

Here are some lessons he shared.

1) Care Should Be Collaborative Instead of 12-Steps Only

Michael went to Graduate School of Social Work at the University of Denver while he was early in his recovery. He described himself during that period as a “12-Step hardliner.”

He wasn’t alone in this. At the time, there was a focus on abstinence and a belief that if someone wasn’t successful in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), they must not have “hit bottom” yet. However, while some people could get sober this way, studies began to show that it was a relatively small percentage of people who were clean and sober after several years with only a hardline 12-Step approach.

While working at the Center for Dependency and Addiction Recovery (CeDAR), Michael found himself collaborating with professionals from a variety of disciplines, including psychiatry, substance abuse, psychology, and social work, family counselors, medical doctors, chaplains, exercise physiologists, and PEER assistance. In many ways, the model resembled that of treating other chronic illnesses, in which many professionals are involved over a longer period of time. He recognized that no one discipline had a monopoly on the solution and that a synthesis of all these approaches was necessary for addiction treatment.

Michael remains incredibly grateful for and involved in the Twelve Step Movement while recognizing its limitations. “It fit me like a glove,” he says while acknowledging that it has limitations and isn’t a fit for everyone.

2) People Don’t Have to “Hit Bottom” Before Recovering

Michael also saw through his own experiences with clients (and echoed in the research) that it wasn’t necessarily true that someone had to “hit bottom” to recover. More important was how they responded to treatment once they got involved—whether they came of their own accord or loved ones intervened, once they got to treatment they had the choice of whether to dig in their heels or use it as an opportunity for growth and reflection. He especially saw the importance of intervening before someone “hit bottom” in certain populations such as adolescents and opiate users, where “the bottom may be six feet down in the ground.”

3) Recovery Has a Greater Purpose than Just Staying Sober

One of the lessons Michael has taken from his own recovery journey is that it is possible to address underlying concerns such as trauma much earlier in the recovery process. He shares, “I had to get help for my unresolved trauma, family of origin issues, sexual problems, anxiety … I had to get help for a lot of things. And I realized that people don’t have to suffer as long as I did. We can start peeling away the layers of the onion a lot sooner and start addressing things like trauma a lot earlier in the process.”

He wants treatment to go beyond simply helping people avoid taking a drink. “If we’re not taking it to higher spiritual and existential levels, what are we doing?” Michael wants people to be looking at what underlies their addiction, and the greater purpose of recovery. He hopes millennial especially will look at their recovery as a gift, and explore how they might change the world with it.

4) Long-Term Care Is Essential for Recovery

Another lesson that Michael has taken from his years in the field is the importance of long-term care. He is quick to note that this is not about making money by keeping people in treatment longer, saying, “Some people in the field will say we’re just hanging onto clients for income. But I’ve never thought about hanging onto one person for income in 25 years. It’s about containment and accountability and consistency. As long as you can keep someone in that, you’re buying them time to save their life, so their brain can heal.” He notes that the brain doesn’t even begin to heal from addiction in the first 90 days of sobriety, making it extremely important to support people well after the three-month mark.

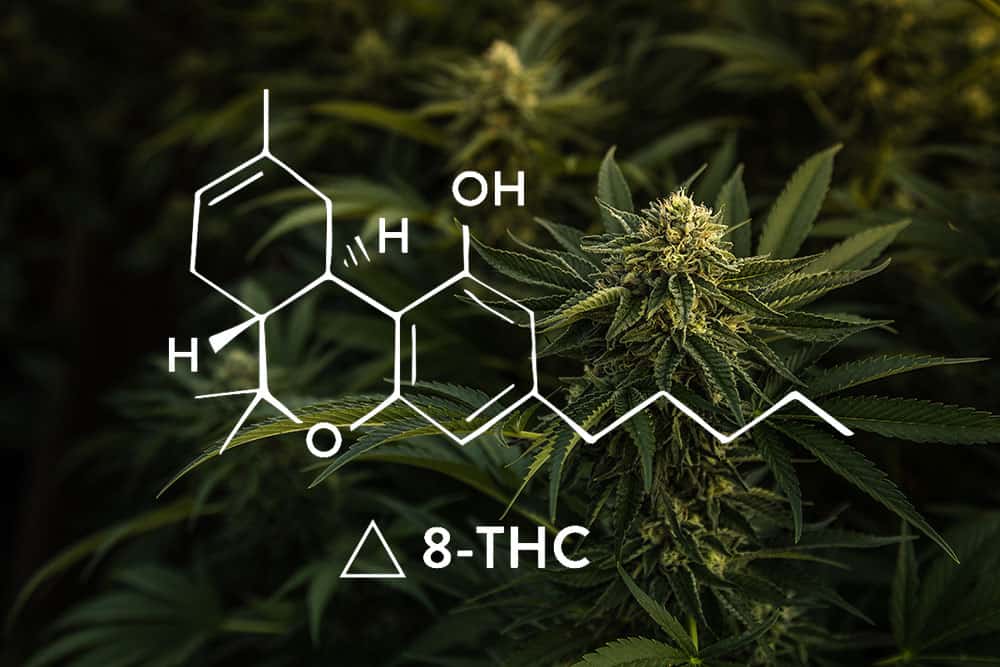

5) Medication-Assisted Treatment Can Be Effective

Michael has also shifted his thinking over time regarding medication-assisted treatment. Whereas early in his career he may have written it off, he now says, “If someone needs to be on Suboxone for 6 months, 9 months, or a year and it helps them learn how to live and connect, get regular with a home group, get a good diet and exercise routine, and realize that their life can be better as they’re coming off of this stuff, I’ll support that.” He adds, “I’m not one for lifetime maintenance and I’m not one for ripping them off their meds within a week just because we do things a certain way. I’m interested in, how do we prevent as many deaths as we can.”

6) Recovery Is More About Progress Than Perfection

One of the things that has shaped Michael’s approach to addiction, in general, is his study of and specialization in process addictions, particularly those that relate to sex and intimacy.

While much of the same criteria used to identify a substance use disorder can be applied to process addictions—signs like an escalation of problem behaviors, withdrawal in their absence, continued use despite adverse consequences, preoccupation, and missing out on life—the treatment is different. While the goal of treating alcohol abuse may be abstinence, the goal of treating out of control sexual behavior is to have a happy, healthy, connected and consensual sexual life. Of sex addiction, Michael explains, “It’s a difficult addiction to treat because you’re walking around with the bottle of vodka in your brain.”

He explains that treatment is about teaching people to work with their thoughts: “We teach them to view any type of craving as a sign and a symptom that something’s off inside of you. It’s not a shaming process.” He continues,

“You can shame someone out of recovery, but you can’t shame someone into recovery. So we have to get rid of these 30 day and 90 day chips—it’s more about progress than perfection.”

In his own recovery journey, Michael has experienced setbacks, as well as a growing understanding that sobriety is not about giving up substances once, but is a continual growth process. He reflects that if he had to have a sobriety date for everything he’s had to give up over the years, “nicotine, shooting my mouth off, being a jerk … my wife says I’d have one for every day of the year.” Instead, Michael has one day a year, August 5, that he goes out on his own and does something like a mountain bike ride, and says, “Thank you, from the bottom of my heart, for waking me up.”

7) Working With Young Adults and Adolescents Requires Humility

“There needs to be a greater humility in working with young adults,” Michael says. “With adolescents, you’re seed planting, and connecting, and showing they can have a relationship with someone that they’re not getting high with, but you have to be humble because you’re probably not going to see these amazing results. When you’re working with adolescents you have to look at recovery as a positive movement.” Michael describes his mother as the kind of therapist that worked with teens in this way.

“It’s more of a systemic thing. You bond with the adolescents and work with the external forces. Parents have a lot of leverage. The really good treatment centers and counselors understand how to use that leverage. They don’t let fear of losing the bond interfere with using the leverage to do what’s right.”

Advice for Those in Recovery

As we wrapped up, I asked Michael if he had any advice for people in recovery:

“Always keep one foot in the things that have worked,” he said. “Don’t be afraid to branch out into meditation, therapy, organizations like Phoenix Multisport. But don’t stop going to your home group, don’t leave AA behind. We don’t talk enough about transition—when times get tough you have to have a group you know and feel comfortable with.”

About Michael Dinneen

Michael Dinneen serves as the Vice President of Business Development for Shadow Mountain Recovery. He is a licensed clinical social worker (LCSW), a certified sex addiction therapist (C-SAT), a certified addiction counselor (CACIII), and has a certificate in Spiritual Direction. He also has extensive training in Emotionally Focused Couples Therapy (EFT) and trauma. Michael has been involved with several prominent different organizations over the years, including the Center for Dependency, Addiction, and Recovery (CeDAR), and Alcoholics Anonymous.