What Is Maladaptive Daydreaming?

Maladaptive daydreaming happens when mental health struggles, negative feelings, or trauma lead to excessive daydreaming as a way to cope with difficult emotions.

It’s normal for people to daydream sometimes.

In fact, some researchers have shown that daydreaming may actually help with relaxation, problem solving, and calming anxiety over time.

But is it possible to daydream too much?

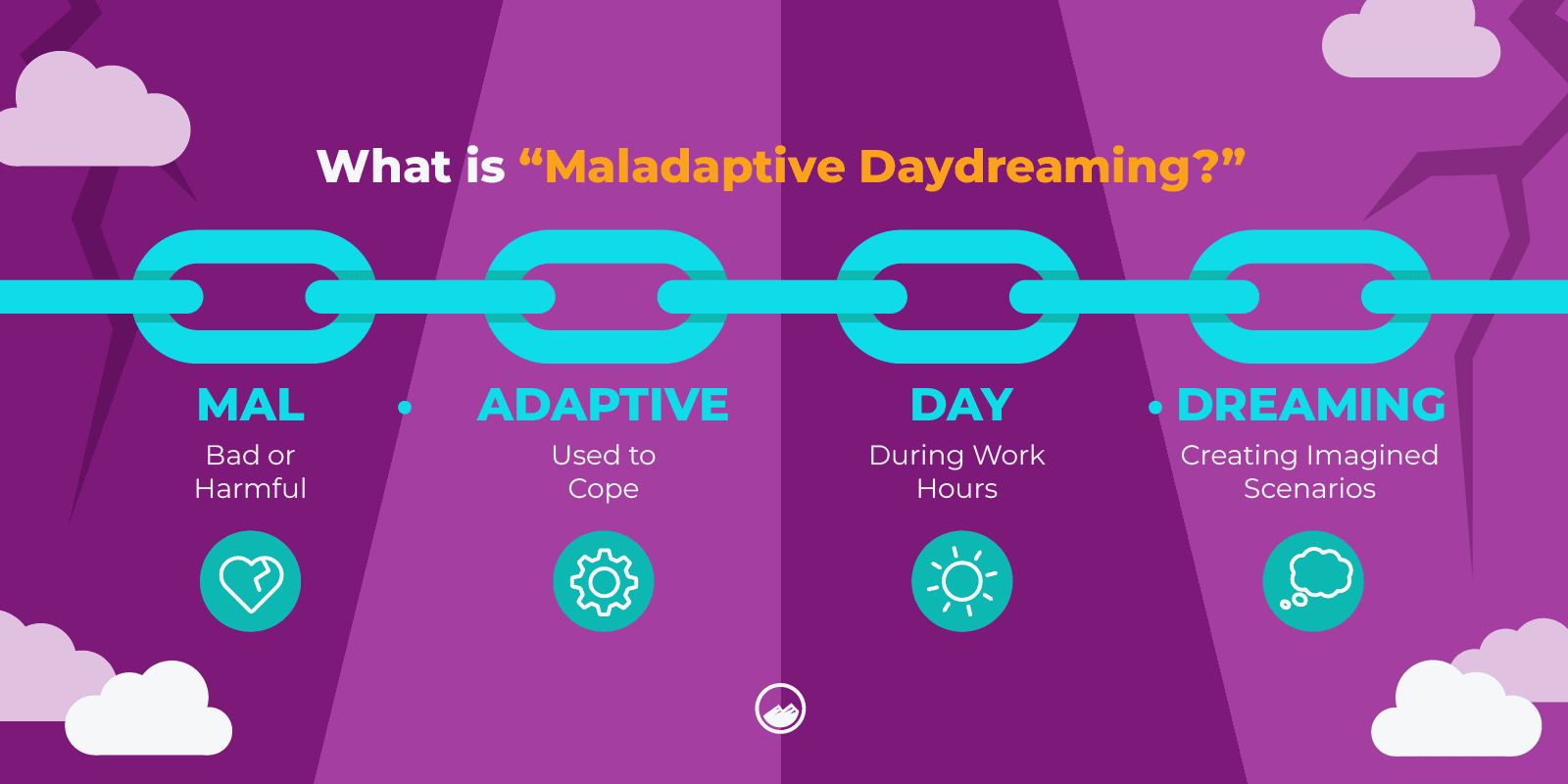

The word ‘maladaptive’ means that a certain behavior has started to make it difficult for a person to function in their daily life.

Maladaptive daydreaming (MD) happens when someone begins to lose themselves in vivid daydreams and fantasy worlds, often for hours at a time.

The time spent excessively daydreaming can make it difficult for them to work, have hobbies, or spend time with loved ones.

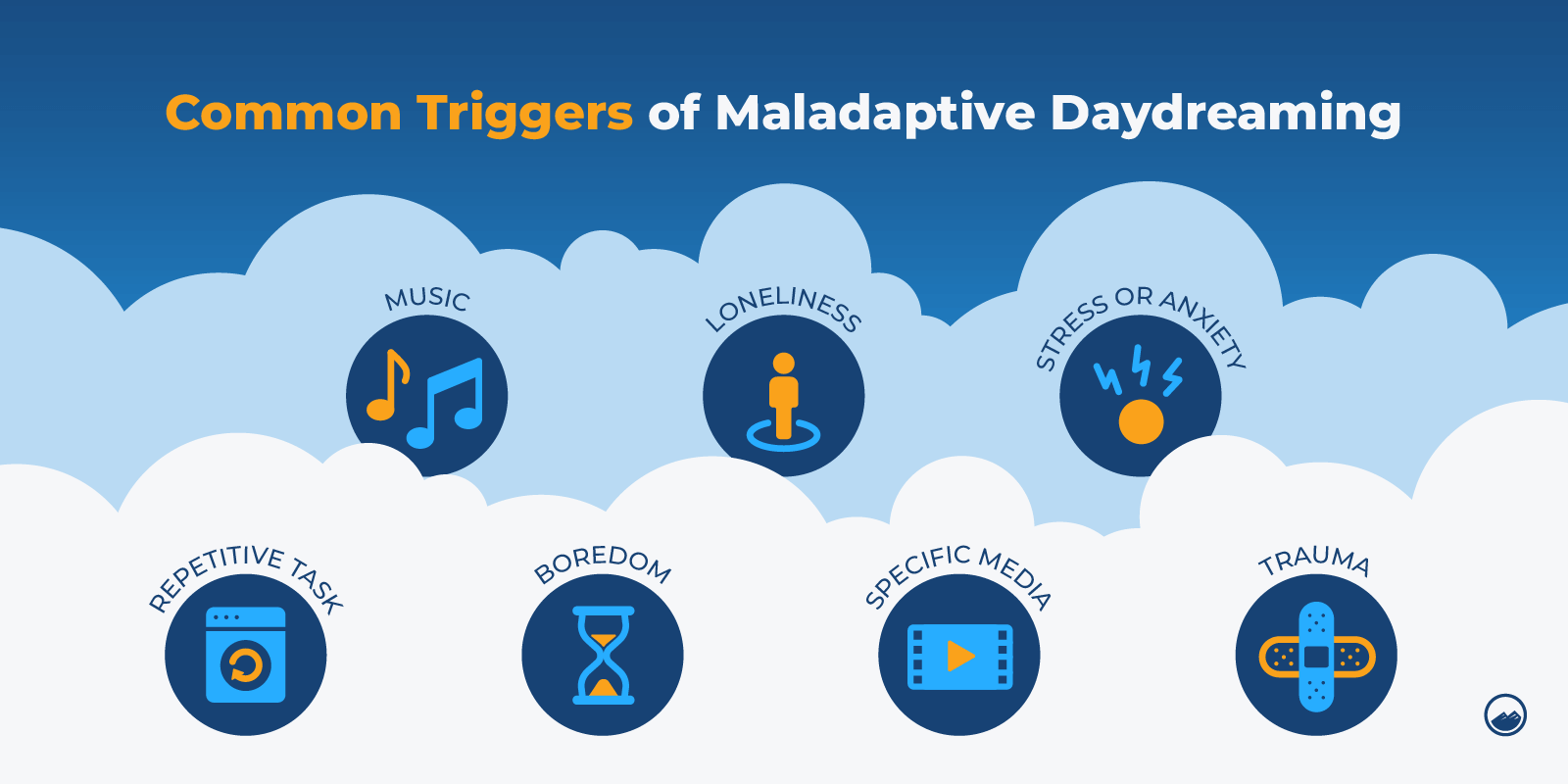

This type of daydreaming is often the result of an underlying mental health condition, such as anxiety. Sometimes it can be triggered by a need to cope with serious life events, such as childhood trauma.

Those with MD may also daydream as a way to escape from uncomfortable situations or to soothe feelings of stress.

While daydreaming as an escape isn’t always unhealthy, those with MD may begin to chronically avoid facing difficult situations, conversations, or life decisions.

Is Maladaptive Daydreaming a Mental Illness?

Maladaptive daydreaming is not considered a mental illness by those in the psychiatry field. However, it is considered a symptom of an underlying mental health issue.

People with maladaptive daydreaming may daydream as a result of experiences like trauma, but they do not always consciously choose to be daydreaming.

When navigating a relationship with someone who has MD, it is important to remember that those with mental conditions cannot choose to “just stop” having symptoms.

With the right support, however, they can learn to treat and manage it.

Though not currently recognized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), maladaptive daydreaming is quickly becoming recognized as an important focus of research.

Is Maladaptive Daydreaming Bad?

Maladaptive daydreaming can make it difficult for someone to navigate their day-to-day life. It may also lead them to feel distressed and isolated.

People who struggle with excessive daydreaming will also often feel like they cannot control where their thoughts go, which can be incredibly frustrating

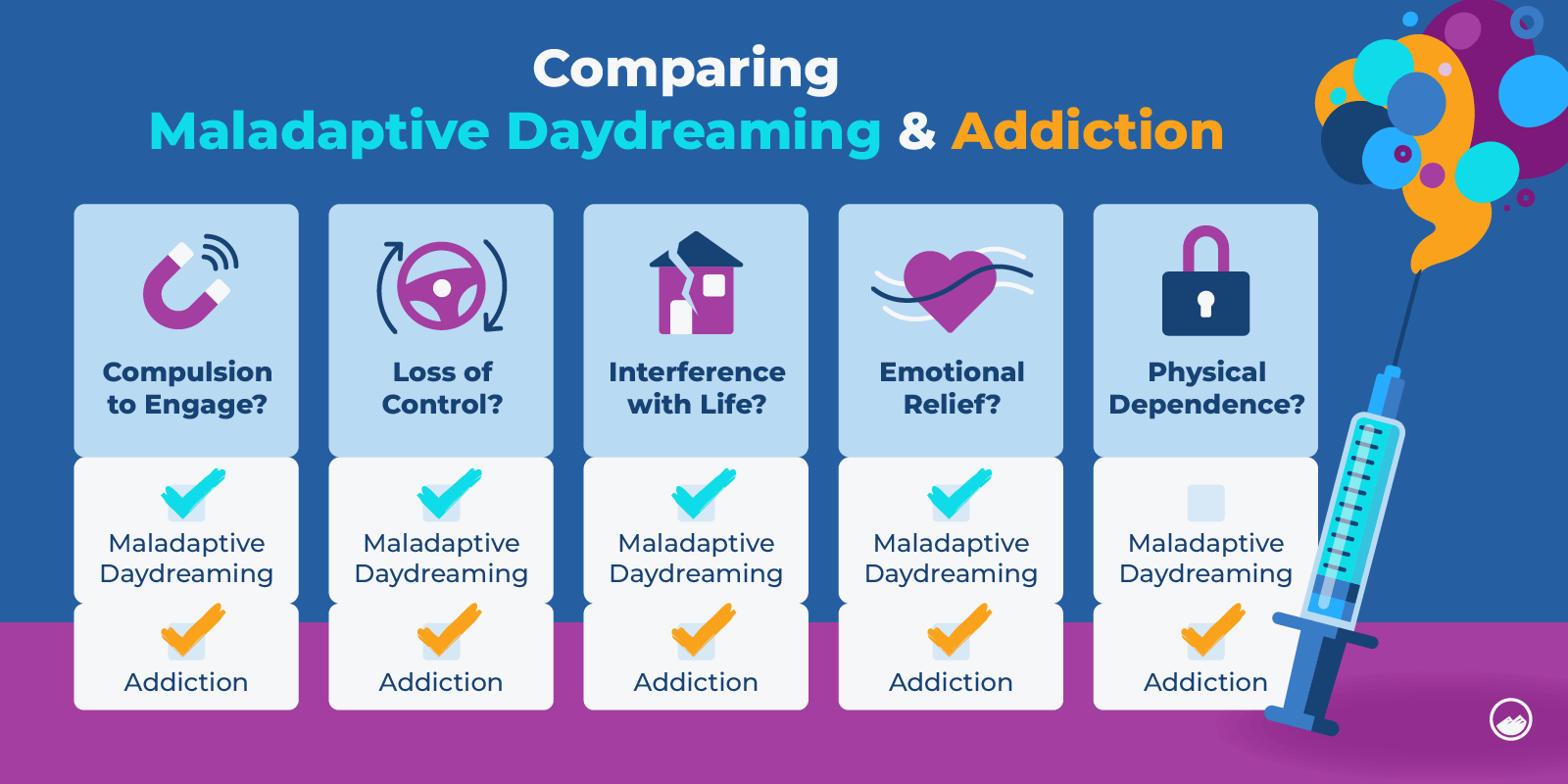

Some research suggests that MD may even be addictive to those who use it to cope with difficult situations.

Those who suffer from MD may eventually feel that they cannot cope with any amount of stress without daydreaming.

The challenges of maladaptive daydreaming can take several forms, such as:

- Interfering with hobbies, work, and studies

- Causing real-world accidents due to being distracted by maladaptive dreaming

- Disrupting social activities and isolating the dreamer

- Feeling shame and guilt, especially when they try to stop or lessen daydreaming but cannot

- Experiencing constant compulsions to daydream

- Feeling distressed when unable to continue the ‘story’ when unable to find the time to daydream, or when the daydream is interrupted

How Rare Is Maladaptive Daydreaming?

While there are no official reports on the prevalence of maladaptive daydreaming in the United States, there is data to suggest it’s more common among those with ADHD.

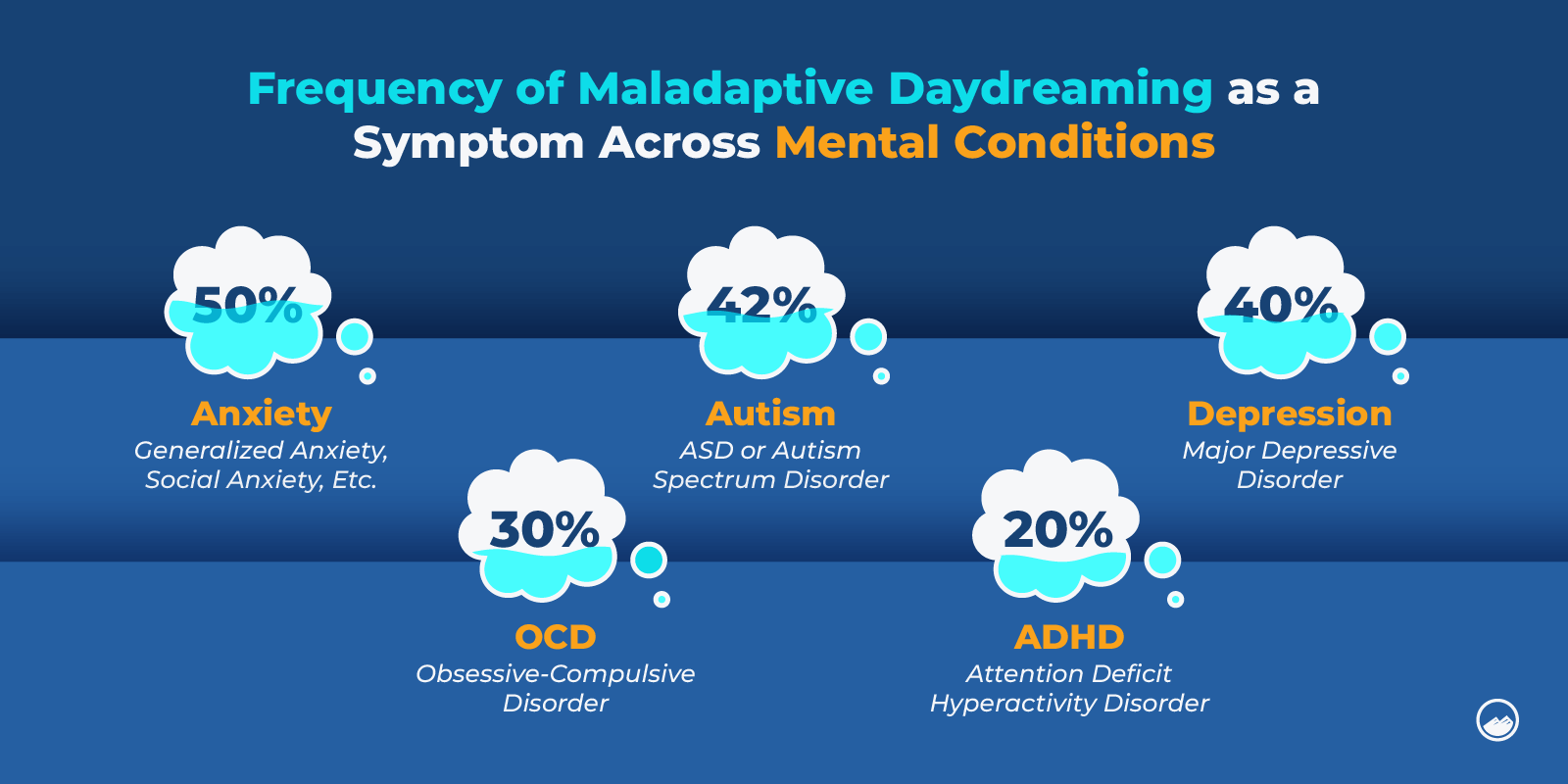

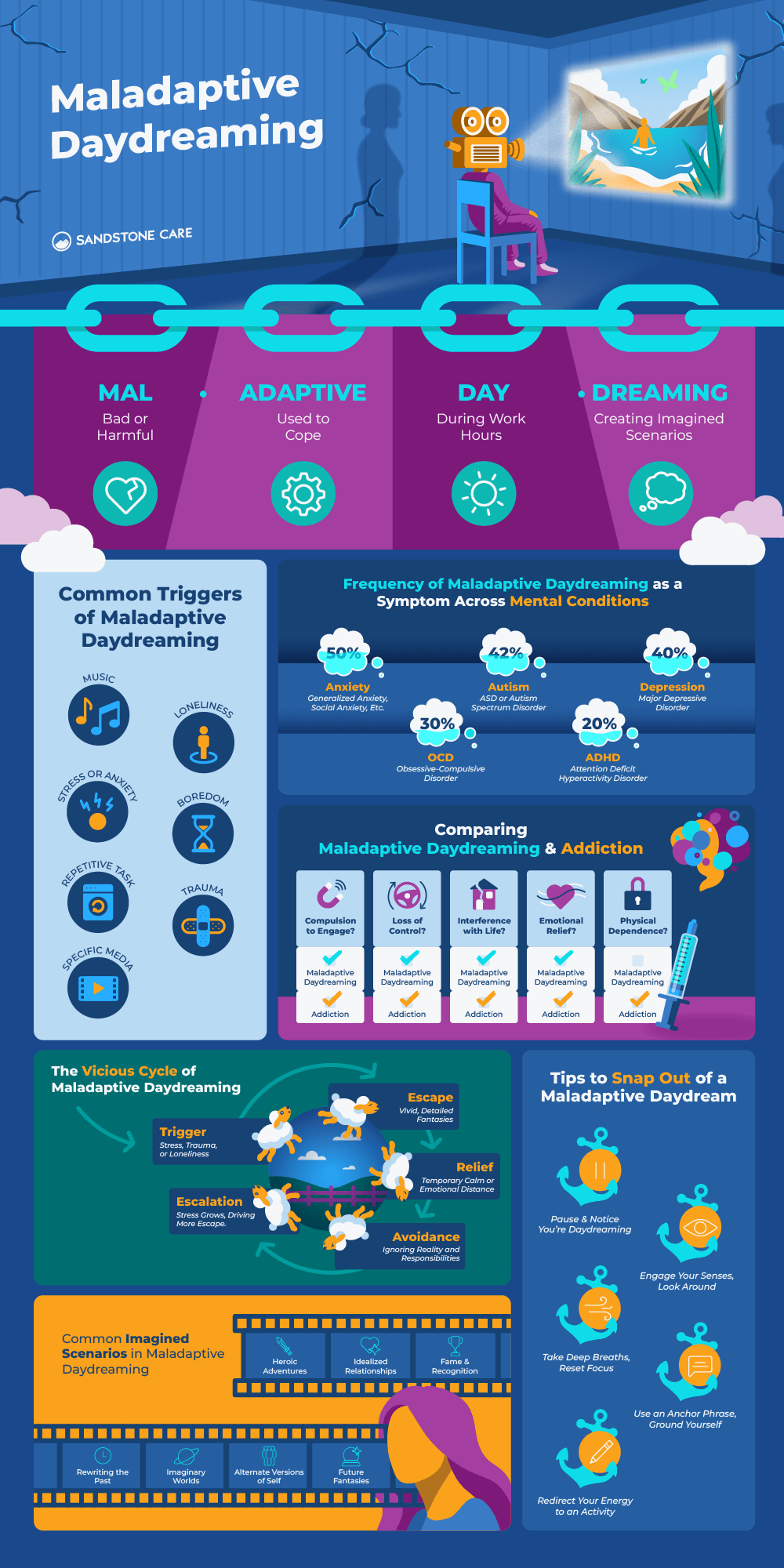

It’s estimated that maladaptive daydreaming affects 20% of adults struggling with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a number that comes out to about 2.2 million adults in the U.S.A.

This number does not account for those who are struggling with maladaptive daydreaming but not ADHD.

Due to the newness of this condition, not much research has been completed yet to give an accurate account of how many people are struggling.

However, Eli Somer, PhD, a clinical psychology professor in Israel, has been studying this condition since he named it in 2002.

Why Is Maladaptive Daydreaming So Addictive?

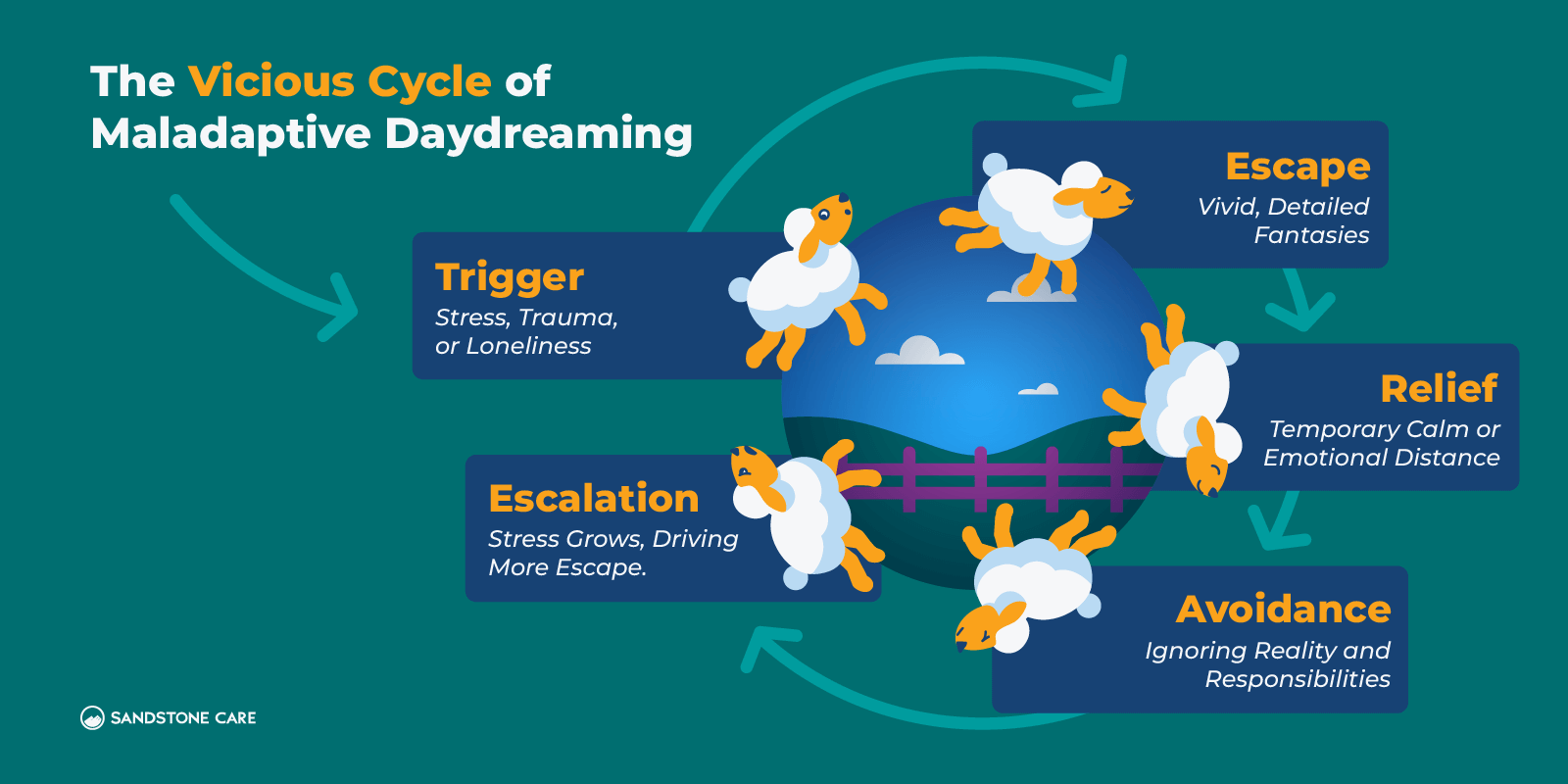

One reason maladaptive daydreaming is so addictive is because it can create a vicious cycle of depending on daydreaming to cope with overwhelming feelings or situations.

As someone uses daydreaming excessively to deal with difficult emotions, they may find they begin to lose the ability to handle those emotions healthily.

This can cause them to turn to daydreaming more often and more quickly, no matter the negative symptoms they begin to experience as a result.

As those with MD struggle to complete their work and social responsibilities because of the time they spend daydreaming, they often find themselves in increasingly stressful situations.

They may turn to daydreaming to cope with these feelings of failure, panic, or isolation, setting off the cycle once again.

One case study has found similar traits between Maladaptive Daydreaming and behavioral addictions through several shared traits, such as:

- Being unable to stop or lessen the behavior despite wanting to

- Having a desire, compulsion, craving, or urge to engage in the behavior

- Feeling distressed or anxious when not able to engage in the behavior

- Constant thoughts of when to engage in the behavior next and how

- Experiencing feelings of elation, euphoria, or pleasure when engaging in the behavior

- Needing to increase the frequency of the behavior to continue to receive the same amount of positive feelings as before

Once a person begins to daydream excessively, it can become difficult to stop without the help of a mental health professional.

Maladaptive Daydreaming Causes

What Causes Maladaptive Daydreaming?

There is no exact cause of maladaptive dreaming, but conditions such as underlying trauma and mental health disorders can put someone at a higher risk of MD.

Maladaptive dreaming is commonly found in mental health disorders known for high rates of anxiety or impairments of certain brain functions, such as executive functioning.

Some mental health conditions that seem to encourage maladaptive daydreaming include:

- Anxiety disorders, especially social anxiety

- Some forms of depression

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Dissociative disorders, such as dissociative identity disorder (DID)

However, maladaptive daydreaming doesn’t always mean that the person struggling with it has a diagnosable mental health condition.

For example, people who are lonely or isolated may also be at risk for maladaptive daydreaming, as well as those who have suffered from trauma.

Some may also find themselves daydreaming excessively to deal with temporary experiences, such as going through the stages of grief.

Is Maladaptive Daydreaming a Coping Mechanism?

Yes, maladaptive daydreaming is an unhealthy coping mechanism used to escape from distressing emotions or situations.

Daydreaming, even when it is done healthily, is known for its ability to help dreamers escape from the boredom or stress of their everyday lives.

However, when it becomes a major way that somebody navigates challenging experiences, this escape can become paralyzing.

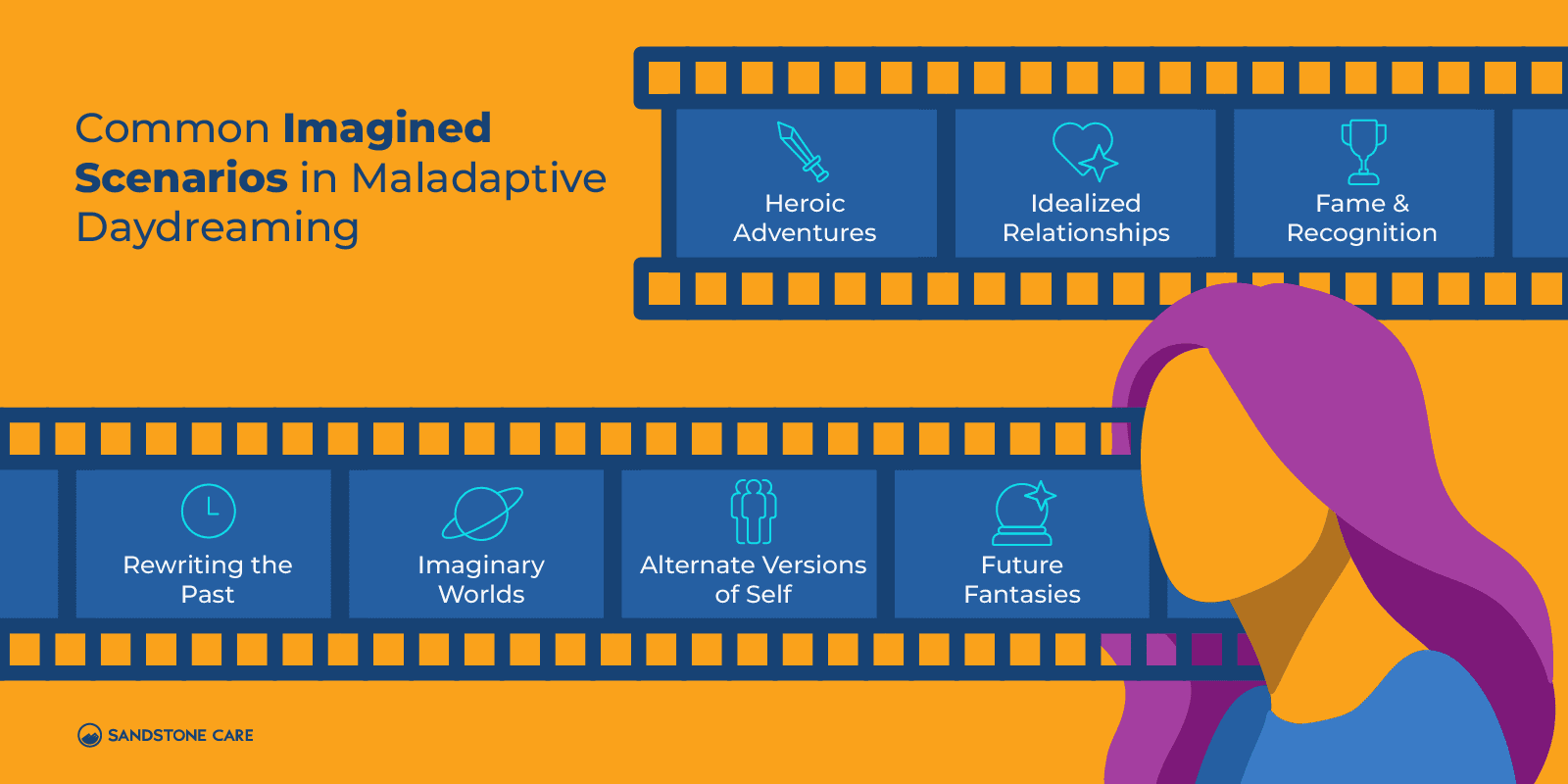

Maladaptive daydreaming is commonly used:

- To Ignore or lessen the effects of a mental health disorder or trauma

- As a way to cope with trauma by building elaborate fantasy worlds or rewriting history

- To escape uncomfortable or frightening situations by retreating into an inner world

- As a way to escape the real-life effects of isolation and loneliness

- To lessen the impact of stress or pain

What Kind of Trauma Causes Maladaptive Daydreaming?

Childhood trauma is, by far, the type of trauma most responsible for maladaptive daydreaming.

However, any other form of trauma may also cause a person to develop maladaptive daydreaming as a coping method.

What Is the Link Between Maladaptive Daydreaming and ADHD?

Maladaptive daydreaming is found in approximately 77% of people who meet the criteria for the inattentive sub-type of ADHD.

Those with ADHD tend to experience spontaneous mind wandering more often than people without the condition due to an unconscious effort from the brain to search for more stimulating tasks over less stimulating ones.

However, some believe that MD may be a distinct disorder and not just a symptom of ADHD.

What Is the Link Between Maladaptive Daydreaming and Autism?

42% of adults with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) also experience symptoms of maladaptive daydreaming.

Though the cause is not clear, there is a recognizable connection between ASD and MD with shared traits such as:

- Difficulties with emotional regulation and social interaction

- Repetitive movement and/or facial expressions (“stimming”)

Does OCD Cause Maladaptive Daydreaming?

Obsessive-compulsive disorder does not cause maladaptive daydreaming, although maladaptive daydreaming may be a symptom of OCD.

Those living with OCD may feel the urge to excessively daydream to escape the fear and anxiety caused by their obsessions.

In time, maladaptive dreaming can become distressing to those with OCD due to the increasing lack of control over their compulsions to daydream.

Maladaptive Daydreaming Symptoms

What Are the Symptoms of Maladaptive Daydreaming?

Symptoms of maladaptive daydreaming include:

- Extremely intense and vivid daydreams

- Daydreams that are accompanied by repetitive movements

- Suffering from sleep problems or difficulty falling asleep due to daydreaming

- Elaborate and complex daydreams that follow a ‘story,’ which often includes many other people

- Daydreams that last for long periods, which take up most of the dreamer’s waking hours

- Feelings of disconnect from others and real life while daydreaming

Maladaptive daydreaming also causes damage to mental health by causing feelings of shame and distress.

It may also cause harm to a person’s social life, employment, and schooling, making it difficult to function.

Maladaptive dreamers are caught in a cycle of wanting to stop their behavior but are unable to overcome the compulsion on their own.

How Do You Know If You Have Maladaptive Daydreaming Disorder?

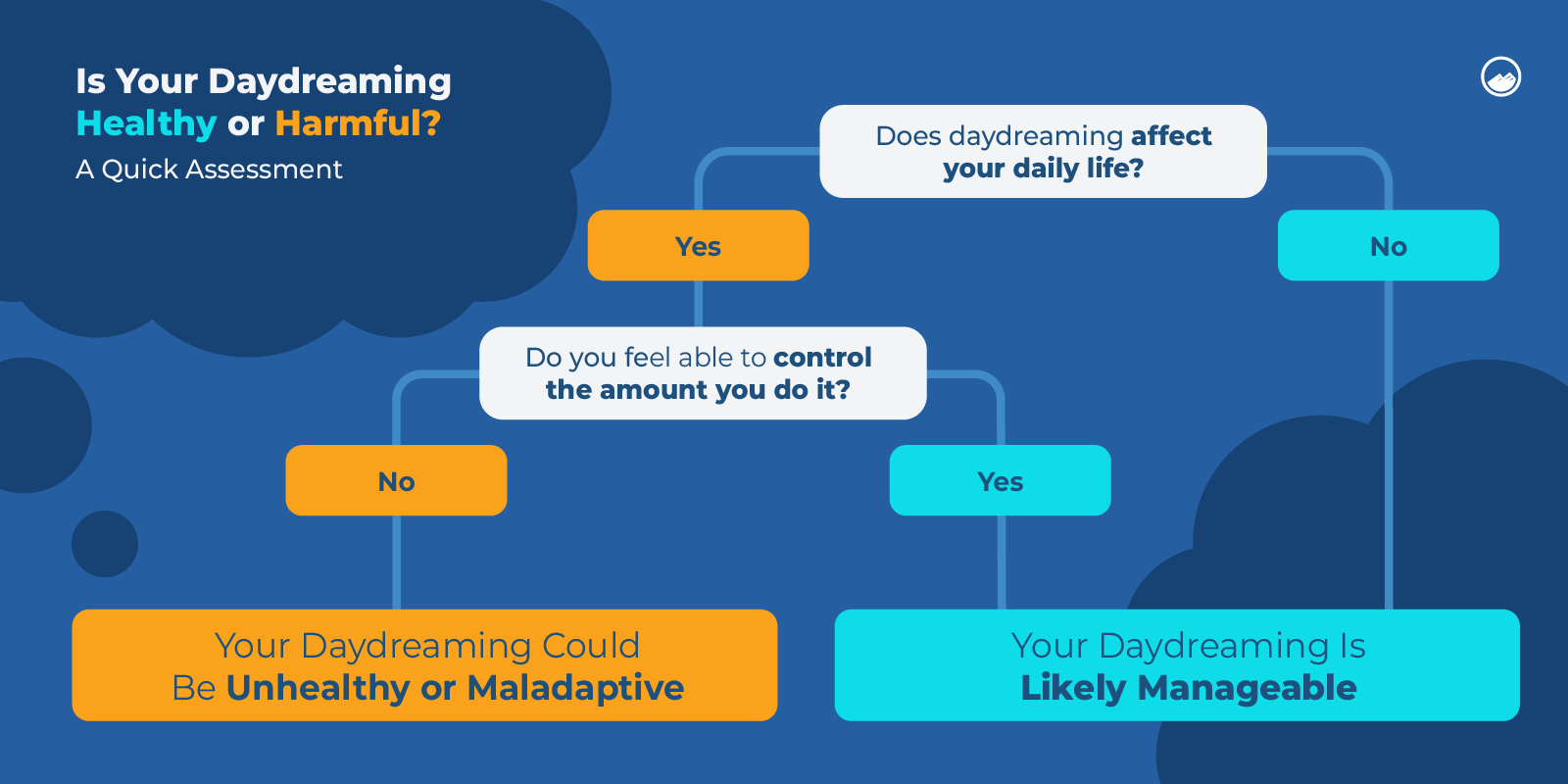

If you cannot stop daydreaming, even when it is causing harm to your life and mental health, you may suffer from maladaptive daydreaming disorder.

A self-assessment questionnaire tool called Maladaptive Daydreaming Scale-16 (MDS-16) exists to help doctors and self-assessors determine if daydreams have become harmful.

The MDS-16 contains a series of questions that patients answer to evaluate their daydreams over the past month.

Some questions include:

- How distressed do you feel when you are unable to find time to daydream?

- Has daydreaming ever interfered with your occupational or academic success?

- How strong is your urge to return to a daydream once it ends or is interrupted?

- Can you accomplish goals, chores, or tasks without daydreaming or feeling the urge to daydream?

Doctors and those looking to self-assess will then tally the score. The higher the score, the more likely the person is experiencing maladaptive daydreaming.

The MDS-16 is not a diagnostic tool, however, and people should seek the help of a certified mental health professional if their daydreaming is causing harm and distress.

Do Maladaptive Daydreamers Know They’re Daydreaming?

Yes. A person engaging in maladaptive daydreaming knows they are daydreaming and does not confuse it with reality.

Though the dreamer may wish their daydreams are real, they are always aware that they aren’t.

A person daydreaming, however, may choose to ignore outside stimuli in favor of their daydream.

This is not the same as a dissociation or complete loss of reality, like a delusion.

What Are Examples of Maladaptive Daydreaming?

Some examples of maladaptive daydreaming are:

- Losing job opportunities and failing essential tasks because of consistently daydreaming throughout the workday

- Missing classes or failing exams due to a loss in sleep quality because of the urge to daydream instead of rest

- Becoming injured while performing household tasks because of the distraction of daydreaming while repairing things.

- Isolating from loved ones to daydream without interruptions, leaving friends and family concerned.

Scenarios in which maladaptive dreaming can be dangerous are endless.

The common link between all these examples is that excessive daydreaming is causing severe damage to their social, mental, and physical health.

Maladaptive Daydreaming Vs. Daydreaming

What Is the Difference Between Maladaptive Daydreaming and Daydreaming?

A person who daydreams normally only spends a quarter of their waking hours daydreaming, compared to a maladaptive daydreamer, who will spend half their waking hours or more daydreaming.

Normal daydreaming occurs entirely in the mind, with the only outside sign being a lack of focus or being visibly distracted.

Maladaptive daydreaming is highly immersive and often accompanied by verbalizations, facial expressions, and repetitive movements.

When Does Daydreaming Become a Problem?

Daydreaming becomes a problem when it interferes with a person’s ability to function and participate in daily life.

People struggling with MD will sometimes lose jobs, neglect their health, or even suffer from physical harm from accidents due to excessive daydreaming.

Maladaptive Daydreaming Vs. Dissociation

Is Maladaptive Daydreaming Dissociation?

No, dissociation is different from maladaptive daydreaming.

Maladaptive daydreamers are aware that they are daydreaming, though they may ignore reality so as not to ‘interrupt’ the daydream. A person who is dissociating experiences a disconnection from their sense of self, thoughts, and sensory experiences.

Am I Dissociating or Daydreaming?

If you are aware of the reality that you are daydreaming, you are not dissociating.

Dissociation is a disconnection or detachment from one’s surroundings or sense of self, usually triggered by trauma or a dissociative disorder.

A person who experiences dissociation can still daydream normally or abnormally.

Effects of Maladaptive Daydreaming

What Are the Short-Term Effects of Maladaptive Daydreaming?

Short-term effects may include:

- Difficulties in focusing on tasks

- Exhaustion from lack of restful sleep

- Difficulties in being productive in studies, work, or household management

- Friction between loved ones and real-life relationships

- Feeling stressed or anxious

What Are the Long-Term Effects of Maladaptive Daydreaming?

Long-term effects may include:

- Losing a job or flunking out of school.

- Loss of personal real-life relationships

- Worsening physical and mental health, including exasperating existing mental health conditions

- Failing to meet set goals and milestones

- Constant feelings of stress, anxiety, or shame

- Feeling an increasing compulsion to daydream

- Increased risk of physical harm due to accidents

Can Maladaptive Daydreaming Lead to Schizophrenia?

There is no current evidence that maladaptive daydreaming can lead to schizophrenia.

People with MD are aware that their daydreams are not real, while people with schizophrenia perceive their hallucinations as real.

Hallucinations are not controllable and are often frightening experiences compared to daydreams, which can be initiated on command and are usually pleasant.

How to Stop Maladaptive Daydreaming

How Do I Prevent Maladaptive Daydreaming?

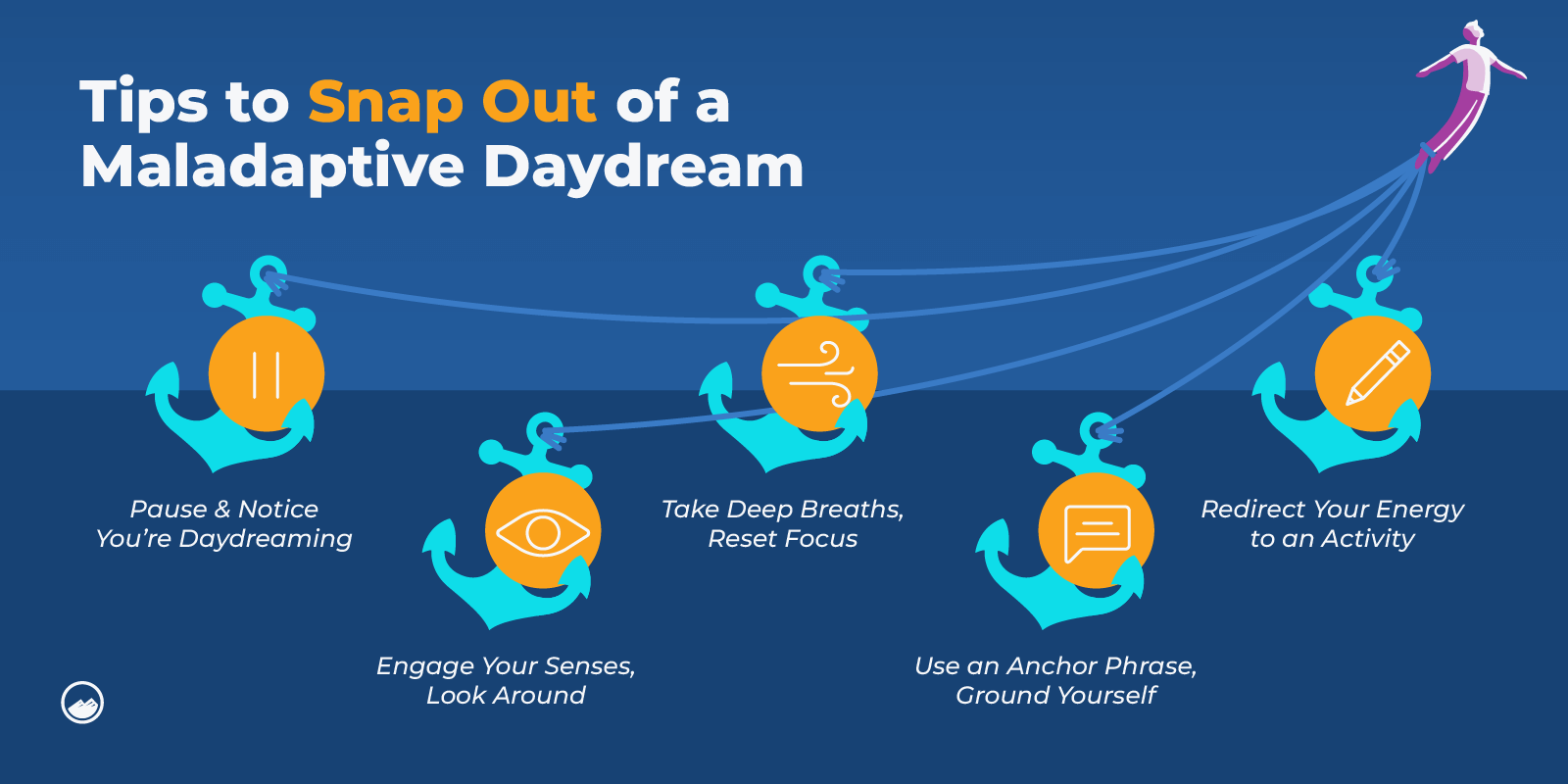

The best way to prevent maladaptive daydreaming is to be aware of what healthy and unhealthy daydreaming looks like.

Being educated on the common signs of out-of-control daydreaming allows people to seek help before it can severely impact their lives.

Improving physical and mental health can also prevent, as well as treat, maladaptive daydreaming.

Some of these preventative strategies are:

- Reducing stress

- Learning and practicing healthy coping skills

- Regular exercise

- Switching to a healthy, nutritious diet

- Regular exposure to sunlight as a mood booster

- Getting proper rest and sleep

- Having a support network of friends and family

Will Maladaptive Daydreaming Ever Go Away?

Yes. Anyone can recover from compulsive MD with professional help and a willingness to put in the effort to find new and healthy coping skills.

With treatment and the aid of a mental health professional, a person can reduce, control, or eliminate their urges to compulsively daydream.

What Is the Best Way to Treat Maladaptive Daydreaming?

Psychotherapies, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), are the most common way to treat MD.

CBT is also used to treat conditions that co-occur with MD, such as anxiety, depression, and OCD.

This therapy works by helping people identify what triggers them to compulsively daydream. Then, they work on understanding why they want to daydream.

Finally, they learn how to cope with and manage the urge to daydream.

Trauma-based therapies are also effective for those who daydream as a result of trauma.

What Medication Is Used for Maladaptive Daydreaming?

Fluvoxamine, a medication used to treat OCD, has been shown to alleviate symptoms of MD.

Anti-anxiety, antidepressant, and anti-psychotic medications may also assist those struggling with MD.

However, not everyone will need medication to treat MD in specific, just their underlying mental health conditions.