Enabler Definition

What Is an Enabler?

An enabler is a person who allows someone close to them to continue unhealthy or self-destructive patterns of behavior.

Enabling can look like being a cover up for others, helping them avoid taking responsibility for their own actions, or feeling too nervous to set boundaries.

Many people who are enablers may not be trying to be or be aware that they are enabling their loved ones.

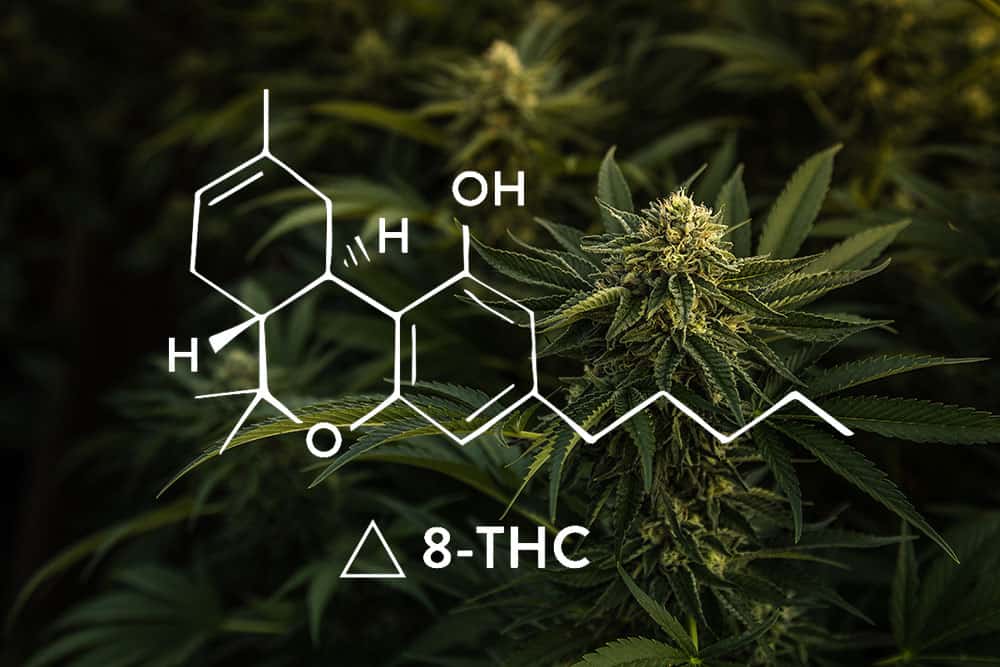

When the term enabler is used, it is usually referring to drug addiction or alcohol misuse.

However, an enabler can be associated with any person who supports harmful behavior and makes it easier for the person to continue their behaviors.

Not to be confused, enabling doesn’t mean that a person thinks the behaviors of the other person are okay, but they might tolerate them because they don’t know how to better handle the situation.

A person might be an enabler for a variety of reasons. However, it is often because they think that things will get worse if they aren’t there for their loved ones in the way they think they need them.

What Is the Difference Between a Helper and an Enabler?

One of the distinct differences between a helper and an enabler is that a helper does things for others when that person can’t do it themselves. An enabler does things that the person should be able to do for themselves.

For example, a helper might assist a loved one in finding a therapist or attending support meetings if they’re struggling with mental health or substance use issues.

An enabler, however, might repeatedly call in sick for that loved one at work or make excuses for their behavior, preventing them from facing consequences or taking accountability for their own life.

Helpers encourage progress, while enablers often maintain the status quo.

What Is an Enabling Behavior?

Enabling behavior is when someone unintentionally supports or encourages another person’s harmful habits or choices.

This often happens out of a desire to help or protect close relationships, but it actually ends up preventing the person from facing the consequences of their actions or taking responsibility.

For example, giving money to a loved one who uses it for drugs or alcohol, or covering for someone’s bad behavior, are forms of enabling.

While it might feel like you’re helping in the moment, this behavior often makes it harder for the addicted person to change or grow.

What Is an Enabler Personality?

Someone with an enabler personality has a desire to help others, so much so that they would help them even when their behaviors can harm them.

They often step in to fix problems, shield loved ones from consequences, or avoid conflict, even when it causes them stress or exhaustion.

Over time, this behavior can lead to toxic relationships, where one person becomes dependent and less accountable, and the enabler feels trapped or taken advantage of.

This can also lead to a type of trauma bonding, where the enabler feels that they cannot stop enabling the person that they love without feeling that they abandoned them in their time of need.

For the enabler, this can be emotionally draining and damaging to their self-esteem.

They might think, “If I don’t step in, everything will fall apart,” but this mindset keeps them stuck in a cycle of overgiving while the other person avoids responsibility.

Without setting healthy boundaries, these patterns can prevent both people from growing and lead to frustration, resentment, and burnout.

Is Being an Enabler Positive or Negative?

Being an enabler doesn’t mean that someone is a bad person, but it isn’t a healthy thing for either them or the person that they are trying to take care of.

Often, enabling starts when a person tries to offer support to someone they care about because they know they are going through a difficult time.

Unfortunately, most people don’t have the skillset to navigate things like addiction appropriately.

It can quickly turn into a draining and unhealthy relationship when loved ones try to provide support they aren’t qualified for.

This is why it is so important to encourage loved ones to seek things like addiction treatment, support groups, or detox opportunities so that they can get the help they need from health professionals.

What Is Negative Enabling?

Negative enabling happens when someone unintentionally supports harmful behavior by shielding a person from the consequences of their actions.

For example, imagine a parent whose adult child is struggling with substance use.

The young adult spends their money on drugs or alcohol, and when they can’t pay their rent, the parent steps in to cover it.

The parent might justify this by thinking, “If I don’t help, they’ll end up homeless,” but by consistently bailing them out, the parent makes it easier for the child to continue their behavior without facing the financial consequences.

While the parent’s intentions come from a place of love and protection, their actions unintentionally enable the child to avoid responsibility for their choices.

This not only allows the harmful behavior to continue but also creates stress, guilt, and resentment for the parent, trapping both in an unhealthy cycle.

Breaking this pattern requires setting firm boundaries and encouraging the child to take responsibility for their own recovery.

Is this blog hitting close to home?

We’re here to help.

Characteristics of Enablers

What Are the Characteristics of an Enabler?

Some of the most common characteristics of an enabler can include:

- Overly Compassionate

- Conflict-Averse

- Self-Sacrificing

- Overly Responsible

- Highly Loyal

- Optimistic to a Fault

- People-Pleasing

- Fearful of Rejection

- Overprotective

What Is the Psychology Behind Enablers?

The psychology behind enablers often comes from a mix of past experiences, traumas, family dynamics, and personality types.

Many enablers grow up in situations where they feel responsible for keeping the peace, solving problems, or making others happy.

Generational trauma is one example—patterns like “family always takes care of each other” can be passed down in ways that discourage healthy boundaries or accountability.

Parenting styles, like being overly protective or neglectful, and experiences of abuse can also lead someone to prioritize others’ needs over their own to avoid conflict or feel valued.

For example, an adult sibling who grew up with a parent struggling with addiction might have learned to avoid conflict and “fix” problems to hold the family together.

As an adult, they might enable a brother’s substance use by calling his boss to make excuses when he misses work.

They might think, “It’s my job to protect him because we’re family,” but in reality, they’re shielding him from the consequences he needs to face to grow.

Enablers often act out of love, guilt, or fear of losing the relationship, but this behavior creates unhealthy patterns.

It keeps both people stuck—one avoiding responsibility and the other carrying more than they should.

Recognizing where this behavior comes from and setting healthy boundaries is the first step toward breaking the cycle and building healthier, stronger relationships.

Do Enablers Lack Empathy?

No, usually enablers have a heightened sense of empathy, which is why it can be difficult for them to hold the other person accountable or allow them to face consequences.

An enabler might feel a high sense of empathy, which causes them to do anything they can to make the person happy or to diffuse the situation, even if that means allowing them to continuously engage in harmful behaviors.

Is an Enabler a Narcissist?

An enabler is not commonly a narcissist. However, enablers can be victims of narcissistic abuse, or people can be enablers to individuals with narcissistic personality disorder (NPD).

For example, a narcissistic enabler might protect a narcissist from facing the consequences of their actions.

Four Types of Enabling

Caretaking Enabling

A person who engages in caretaking enabling provides constant care to another person in hopes that they can protect that person from harm.

For example, a parent of an adult child with substance use issues might prepare all their meals, clean their home, and handle their bills, thinking, “If I take care of everything, they won’t spiral further.”

While the intention is to help, this behavior allows the harmful cycle to continue and can lead to burnout for the caretaker.

Protective Enabling

Protecting enabling involves shielding the other person from the consequences of their actions. This might look like covering up their behaviors or lying to protect them.

For example, a spouse might lie to their partner’s boss, saying they’re sick, when the real reason they missed work was due to excessive drinking.

The enabler might think, “I’m just trying to protect them from losing their job,” but this behavior only allows the problem to persist and delays the need for change.

Rescue Enabling

A rescuing enabler intervenes or helps the person whenever a problem comes up, taking on that person’s responsibilities when they should be working through that problem themselves.

For example, a friend might repeatedly loan money to someone who overspends, thinking, “If I don’t help, they’ll be in serious trouble.”

Instead of learning to budget or manage their finances, the person becomes reliant on the rescuer, continuing the problem and creating an unhealthy dynamic.

Overcompensation Enabling

Overcompensating involves neglecting one’s own needs and taking on the responsibilities and tasks of another person. They try to overcompensate for the other person.

For example, a partner might take on all the household chores and bills because their spouse refuses to contribute, thinking, “If I don’t do it, nothing will get done.”

While this may keep things running smoothly in the short term, it allows the other person to avoid their responsibilities and creates an imbalance in the relationship.

Stages of Enabling

Not all experts agree on the amount of stages when it comes to enabling, but some include denial, compliance, control, and crisis.

Other experts label the stages as innocent enabling and desperate enabling.

Denial

In the denial stage of enabling, the enabler tries to downplay or deny that there is a problem or that their actions are potentially harmful and unhealthy.

This stage is often rooted in fear, guilt, or a desire to avoid conflict, and it prevents both the enabler and the other person from addressing the issue.

For example, a parent might insist, “They’re just going through a rough patch; it’s not that bad,” even as their child’s substance use becomes more obvious.

By downplaying the seriousness of the situation, the enabler avoids facing uncomfortable truths, but this denial only allows the harmful behavior to continue unchecked.

Compliance

In the compliance stage, the enabler tries to comply or accommodate the other person’s destructive behaviors.

This often stems from a desire to keep the peace, diffuse tension, or avoid conflict, even though it continues unhealthy situations.

For example, a partner might agree to buy alcohol for someone struggling with drinking, thinking, “If I don’t do it, they’ll get angry or find a way to get it anyway.”

While this compliance may seem like a temporary solution, it ultimately makes the situation worse.

Control

In the control stage, the enabler tries to take control of the situation.

This can mean that they might keep the person from facing the consequences of their actions or resolve the other person’s problems themselves.

For example, a parent might repeatedly do their teenage child’s homework for them, thinking, “If I don’t help, they’ll fail their class and fall behind.”

While the intention is to support the child, this behavior keeps them from learning responsibility, problem-solving skills, and the ability to manage their own challenges.

Over time, this type of helicopter parenting can prevent the child from building confidence in their abilities.

Crisis

In the crisis stage, the enabler is in a state of stress, and the other person’s destructive actions are catching up, causing the enabler to realize the severity of the problem and how their enabling impacts everyone involved.

For example, a parent who has been covering for their adult child’s substance use may suddenly face the reality when the child gets arrested or loses their job.

The parent might think, “I’ve been trying so hard to help, but now I see it’s only made things worse.”

This stage is often filled with guilt, frustration, and overwhelming stress, but it can also be the first step toward acknowledging the need for change and setting healthier boundaries.

Innocent Enabling

In the innocent enabling stage, a person starts with love and concern for the other person, but they don’t know how to guide or help them.

Desperate Enabling

In the desperate stage of enabling, the enabler is primarily motivated by fear.

Desperate enabling causes stress and difficult challenges for everyone involved. An enabler might do things because they fear that things will be worse if they don’t help them in the way that they do.

Examples of Enabling

Enabling Substance Abuse and Addiction

Enabling is very commonly seen in the context of substance abuse, substance use disorders, and addiction.

It can be very difficult to see a loved one face challenges with substance abuse. A person may want to help but at the same time not know when they need to set a boundary.

For example, an enabler might protect a person from facing the consequences of their actions and addiction because they think that that is the only way to keep them safe. However, this ends up in the other person continuing their destructive and addictive behaviors, and the situation worsening over time.

Enabling Financial Dependency

With financial dependency, a person might provide excessive support for another person, causing them to not face the full consequences of their actions.

For example, this might look like constantly paying off the other person’s debts or irresponsible spending habits.

Enabling Emotional and Psychological Dependencies

Emotional and psychological dependencies might be seen in a romantic relationship or a relationship between a parent and child.

With codependency, a person relies on the other person for support in essentially all aspects of their life, especially emotionally.

A person might become an enabler because they are codependent on them or vice versa, and they feel like the only way to maintain the emotional attachment is by allowing them to do whatever they think makes them happy, even if it is hurting them.

Enabling Overprotective Parenting

According to studies, overprotective parenting is defined as a parent being overly restrictive in an attempt to protect their child from potential harm or risk.

While parents should protect their children, overprotective parenting is excessive and often shields the child from learning from experiences and important life lessons.

An overprotective parent may become an enabler when they allow their child, even an adult child, to neglect responsibilities or continue doing things that are harmful to them.

Causes of Enabling Behavior

What Causes Enabling Behavior?

Often, enabling behaviors come from the desire to help a loved one.

It is not uncommon for enablers to be unaware that what they are doing is actually unhelpful and allow the other person to continue their harmful behaviors.

Other factors that can contribute to enabling a loved one can include:

- Codependent traits

- Low self-esteem

- History of abuse or neglect

- Anxious attachment style

- Living with personality disorders

What Motivates Enablers?

Some reasons why a person might be an enabler can include:

- A fear of conflict

- Feeling a sense of duty or loyalty to the other person

- Cultural norms and factors that lead a person to believe that certain behaviors are okay

- Feeling a sense of hope or optimism that the person will change, even if it is unrealistic

Why Do People Enable Bad Behavior?

People may engage in bad behavior for a number of different reasons.

They might be scared they will lose the other person if they act any differently, they might think they are helping, or they might have grown up learning enabling behaviors from observing the people close to them, among many other reasons.

Signs of Enabling Behavior

What Are Some Common Signs That Someone Might Be an Enabler?

Common signs that someone might be an enabler can include:

- Tolerating problematic behavior

- Making excuses for the other person

- Covering or lying for the other person

- Neglecting their own needs to provide for another person’s needs

- Minimizing the situation

- Denying that there is a problem

- Providing financial assistance or support

- Avoiding conflict

- Feeling resentment towards loved ones

What Is an Example of an Enabler?

An example of an enabler can be someone who supports another person’s alcohol addiction.

Even if they are concerned about the person’s alcohol use, they might continue to encourage their behaviors by going out to drink with them, giving them money when they run out of money due to alcohol use, or lying to other family members and friends about them drinking.

How Do I Know If I Am Enabling Someone?

Sometimes, enablers don’t realize that they aren’t helping the other person and are allowing destructive or unhealthy behaviors to continue.

Some ways to become aware that you are enabling someone is if you are constantly tolerating problematic behaviors, covering for them, lying for them, minimizing the situation, or denying the problem when there is one.

The Effects of Enabling

What Is the Problem With Being an Enabler?

Problems associated with being an enabler can include:

- Emotional exhaustion and distress

- Loss of self-identity

- Resentment

- Financial problems

- Unhealthy coping mechanisms

- Strained relationships with the broader family members and community

Enabling another person’s behavior also can lead to them struggling for longer periods of time, since they never learn the skills they need to break out of the destructive cycle they are in.

If they can rely on their enabler to keep them from facing consequences, it becomes incredibly difficult for them to build a healthier life on their own.

What Are the Risks of Being an Enabler?

One of the biggest risks of being an enabler is that it can end up becoming extremely draining and distressing for both the enabler and the person being enabled.

Being an enabler can take a toll on a person’s mental health, physical health, and overall well-being.

It can also end up in worsened outcomes in relationships and the overall situation, as destructive behaviors continue they come with higher risk.

How to Stop Enabling Behavior

How Do I Support Without Enabling?

The first step in trying to support someone without enabling them is to acknowledge the things you have done that might have allowed the other person to continue their destructive behaviors.

Some tips on supporting someone without enabling is to:

- Set and honor healthy boundaries

- Help empower the other person

- Learn how to say “no.”

- Help them get connected to professional help

How Do You Deal With an Enabler?

To deal with an enabler, it is important to:

- Approach with Compassion

Recognize their actions come from love or fear and use non-confrontational language.For example, say, “I know you’re trying to help, but this might be making things harder in the long run.” - Highlight the Impact

Gently explain how enabling affects both them and the person they’re trying to help, such as preventing accountability or causing personal stress. - Encourage Healthy Boundaries

Suggest ways they can support without enabling, like offering emotional encouragement or resources instead of taking over responsibilities. - Suggest Professional Guidance

Therapy can help enablers understand their behavior’s root causes and learn healthier coping strategies. Family therapy can also address enabling in a group dynamic. - Model Healthy Behavior

Show them what firm but kind boundaries look like by demonstrating it in your own actions and interactions. - Be Patient

Change takes time, and enablers may feel conflicted or resistant. Acknowledge their good intentions and celebrate small steps toward healthier patterns.

How Do You Deal With an Enabler Mother?

When a person has a parent who is an enabler, the parent often relies emotionally on the child, which causes them to make excuses for the child or protect them from the consequences of their actions.

Some ways to deal with an enabler mother or parent can include:

- Setting clear boundaries

- Communicating your concerns and your needs

- Lean on your support system

- Try to stay calm when having a discussion with them

- Seeking professional help

How to Stop Enabling a Mentally Ill Person?

One way to stop enabling a person with a mental health disorder is by first educating yourself on their condition.

Have a solid line of communication that is clear and calm and involves active listening.

Setting boundaries is important in showing someone what you will and will not tolerate, holding them accountable, and avoiding the encouragement of destructive behaviors.

Encourage independence and encourage them to get professional help for their condition.

Help them celebrate their wins and promote healthy behaviors by doing things that are beneficial for both of you.

How Not to Enable Someone With Anxiety?

Some tips to not enable someone with anxiety can include:

- Avoid providing constant reassurance

- Don’t take on their responsibilities as their own

- Set boundaries

- Take care of yourself

- Have clear communication

- Help them get connected to professional help